Thursday, June 26, 1998 -- Lincoln, New Hampshire -

It was just after dinnertime, the July sun was making its way down toward the New Hampshire Mountains - the beginning of the end of this day.

I heard the locomotive steaming toward us from Clark's Trading Post nearby. The steady roll of the iron wheels on the rails and gasping of the steam engine had become a familiar chorus three times a day, carrying tourists on a half-hour ride past the campground. It had become so familiar that I didn't question the fact that the White Mountain Central Railroad has no evening runs.

As the powerful machine chugged past, the bell was silent, and several unusual soundings came from the engineer's horn. They were soft and long, each one ending slowly, blending into a mellow pause before the next one carried on. This I thought odd, as usually the engineer peppers the horn, tugging on the valve line in short, hectic blasts to get the kids on board into a locomotive frenzy and to wake up the Wolfman, who will fire up his heap and buzz the train, doing his best to frighten the children as they laugh at him.

But no, the whistle's song was a soft, mournful sonnet that evening and then, I swear I heard the train stop. Just stop out there in the woods.

The next morning I met W. Murray Clark at his tourist attraction, a seventy-year old favorite of people around New Hampshire. That's the trading post, not Clark - he's seventy-four.

I thought he was the maintenance man, wearing dark blue coveralls and a stern demeanor - looking like he was on his way to fix something. I had told the clerk about T.C.Y. and True America and before I could say "bear paw" I was with Nola Clark, Murray's daughter. She helped explain the Clark story.

Coleman Clark and Florence Murray - the first woman to reach the top of Mount Washington by dog sled - married and had two sons, Murray and Edward, who would grow up around the trading post - at that time selling dog sled rides for ten cents.

1935. Murray and Edward Clark sit with their friend

William MacDonald between them. The bears they are holding are named Toggle, Soggle and Woggle.

(Photo courtesy of Clark's Trading Post)

The two brothers would marry two sisters. Murray had four children and Edward had five children, one of which (also named Edward) would found two tourist railroads nearby and died just a few days before this interview.

Murray took the family business and turned it into a major attraction. They began keeping and showing bears in 1928 (it was not unusual at the time in this area to see caged bears at little stores or gas stations along the road.) He opened the railroad soon after, offering free rides with admission.

Everything the Clarks did (and still do) was about family. Today there are one hundred employees at the trading post and anywhere between twenty and thirty are descendents of Coleman and Florence, depending on who you ask. "We always loved to work here as kids," says Maureen Clark, who started working at the Post at thirteen. "We would rather work here then go to summer camp."

The first job the Clark children get is the official "Cone Carrier." To entice the bears and to reward them during the shows, the trainers hold cones filled with soft-serve ice cream (low butterfat ice milk, actually) and serve a dollop after each trick. So the kid's first job is to stand just outside the ring and, on cue, reach into a cooler, pull out a prepared cone and hand it to one of the trainers. He or she will do this in front of two-hundred other kids who would probably swear off Pop-tarts for life to have this job.

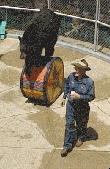

Watch Murray Clark in the ring with his bears and you would think you were watching two brothers joking around. He wrestles with them, teases them, tugs at them, licks from the same ice cream cone - has he forgotten that this animal, nearly three times his weight, has a reputation for eating guys like him?

"You have to love them to teach them, because you will see your own blood," Murray says, of his relationship to his entertainers. Only family members are allowed near the bears. In fact, only his daughter Maureen and son Murray are trainers.

There are seven "working" bears at the Post and the Clarks care for their animals for years after showing them. One has been behind Murray's house for years in "retirement" and Murray still feeds the bear twice a day. "It's commercial for us, yes," Murray says. "But we have a serious responsibility during and after their working years."

Near the train depot, Murray points to several gravestones. "There is Ebony," he says. "she was the mother of Jasper, who sired Ursula, who you saw in the show today."

Three bears laze about their pen at Clark's Trading Post. Are they animals, employees or family? The oldest bear at the Post is nineteen and a half years old.

If you count the visitors, who the Clarks treat like family, you have one of the largest extended families in the northeast. "Some people have been here so many times, we're embarrassed to sell them tickets," says Maureen Clark. The tickets are still quite a deal at only seven dollars for adults. "Some people come here every weekend - Murray has taken at least one couple up to his office and given them lifetime passes."

Often, a family will approach Murray and one of the adults will say; "I came here as a child and I just had to bring my grandchildren to see you." And Murray, without skipping a beat, will interject, "Oh, yes, I remember you." Usually this brings laughter from the clan and sometimes, possibly, they do believe him.

Very community-minded, Murray has been president of the local chamber of commerce, he was in the state legislature for ten years and each year for a week he offers free admission to locals. Years ago, the town needed street signs and Murray had just replaced the bear show ring. So he took the pipes from the old cage and, after work with some friends, would plant them around Lincoln and North Woodstock and hang road names atop them. To this day, you can still see the old Clark's show ring all over town - you may even find Jasper's favorite scratching post.

The Clarks give money to local charities, usually anonymously, and also several small scholarships to students each year. Tourists paying to dump their RV sewage at the Post are actually giving money to this community, as all of the proceeds from the dumping station go to organizations such as the Boy Scouts and the Kancamaugus Recreation Department.

Competition is tough - there are sixteen tourist attractions in the White Mountain region - but the Clarks still pack 'em in, drawing up to two-thousand on a good day. Many come for the museums, displaying antique cars, trains, fire trucks, Americana, cameras, typewriters and even a two-headed calf (lived for three minutes!) Most come to see the bear show.

Murray Clark, giving a great show for his forty-ninth season at the Clark's Trading Post, in Lincoln, New Hampshire.

I have lived in Orlando, Florida for fifteen years, where they train giant whales to dive, roll over and splash innocent kids to music. They choreograph the events to music, lights and fireworks. So, it was indeed charming to watch the Clarks' act.

Murray is the first in the ring and the last to leave. He is a showman and a ham and such a down-to-earth, almost sour, true New Englander, that if you were to call him a showman and a ham, he'd give you a look as though he might just belt you.

A sense of humor dry enough to chap lips, and a flannel-smooth delivery, turn what appears to be a no-nonsense curmungeon into a charming, eloquent showman once he steps in the ring.

Throughout the nearly hour-long show, Murray rolls out one great one-liner after another. Someone had told me "yeah, he tells the same corny jokes year after year." But he tells them because they work. The crowd, mostly families with children, respond with his every move - they watch him intensely.

"We feed the bears dog chow," he says. "But we don't tell them that's what it is - they think it's bear food. We don't want them to start barking." Da-dum.

"Now, bear with me." Da-dum.

"Watch as we play Ursula's favorite game; Bearsketball." Da-dum.

"Sometimes, after eating ice cream too fast, they get a headache and we give them Bear aspirin." Da-dum...bum!

He is as good-natured and as grumpy as you can get, he is a ham and wall flower, and beyond all the contradictions, he is genuine. He is a hard worker and if you ask him what he enjoys about his work most, all you'll get is: "I suppose the end of the day, when I can rest."

Murray deserves rest. Between shows I watch him posing for photographs with children, inspecting a newly installed popcorn wagon, talking with guests and working with his employees. This is his forty-ninth season working this park and he still works it hard.

I ask him if he has ever considered selling the Trading Post, and he interrupts me. "Hell, no!" He says. "It's a family business." Before I leave, Clark glances past his museums, up his railroad tracks, and toward the area where I had heard the train stop on its mysterious journey last evening, and he says; "Buried my cousin, Edward, over there last night, next to my mother."

In Murray Clark's life, the lines blur between his immediate, in-law, distant, employee, bear, community and even patron families, so, except on paper, it's unclear who this little theme park in the White Mountains belongs to.