Tuesday September 14, 1999, Longmont, Colorado -

Have you ever wanted to fly? Not just in an airplane, but on your own wings? To soar above the trees and sail among the clouds? What would you give the person who enabled you to do that? What could you possibly give?

Tuesday September 14, 1999, Longmont, Colorado -

Have you ever wanted to fly? Not just in an airplane, but on your own wings? To soar above the trees and sail among the clouds? What would you give the person who enabled you to do that? What could you possibly give?

Before class, Clark cleans the horse, from his mane to his hooves.

Before class, Clark cleans the horse, from his mane to his hooves.

|

At the Colorado Therapeutic Riding Center, Helen Clark, and hundreds of other volunteers, give wings to people every day. The center, founded in 1980, helps people with disabilities overcome their inabilities. Students who are physically, emotionally or mentally handicapped benefit from a unique bond with the horses.

A horse is not like a mini-bike - you don't just kick-start it and go. First of all, you have to climb up on the huge beast. This may seem easy to you and me, but imagine that you live in a wheelchair, and that you've never even been that high above the ground, let alone atop an animal. Imagine that you are a child, and that you view this world through a lens of fear and uncertainty. It would take a lot to get you on that horse; a lot of courage, confidence and determination. And when you come back down off that horse, you would not be the same person.

Also, a horse's gait resembles that of a human's, so riding helps people with lower body disabilities experience motions and use muscles required for walking. Physical therapists use the center to sometimes even help get people back on their feet again.

Also, a horse's gait resembles that of a human's, so riding helps people with lower body disabilities experience motions and use muscles required for walking. Physical therapists use the center to sometimes even help get people back on their feet again.

Today, Helen Clark is helping a mentally disabled adult named Gary, who likes to go by the name "Cowboy." She has prepared for class by bringing a horse (named Riley) to the corral, along with a set of tack. Clark asks Gary for help putting each piece on the horse. "What is this?" she asks him. "That's right, this is the bridle." She and Gary carefully move each piece from the rail to the horse, and though he is easily distracted, she continues, persistently but gently - her patience is soothing. Four hands are doing the work of two, and two of those hands are doing the work of miracles.

Helen Clark helps her student, Gary, put a saddle on Riley.

Helen Clark helps her student, Gary, put a saddle on Riley.

|

The experience is a positive one for the volunteers, also. Nearing forty, Clark, who also volunteers at an animal shelter, is relaxed and confident in her role. "You get into it, and you get hooked," she says. She also helps feed and clean the horses as a member of the "barn team" and she rides a horse once a week (a policy which gives both the horses and the volunteers a break from their routine.) So, it's a lot like owning a horse, without the expense and as much responsibility. As volunteer Donna Gisle says; "It's not really work; you get your exercise, you work outside and you work with wonderful people." Laura Hodgkins, a teacher and volunteer coordinator for the center sums up her reward; "It has definitely kept my life in perspective."

The center's 20 horses are donated, and are usually retired from other jobs, such as ranching, racing, roping or riding. Many have disabilities of their own, but they all must be what Clark calls "bomb proof." They are teased, taunted and tested for 30 days before a student goes near them. Staff members toss beanie babies at a horse, bump it's legs with wheelchairs and have an instructor climb on it, then mimic a seizure. An important part of the program is the horse's apparent danger, but the center keeps the actual danger to a minimum.

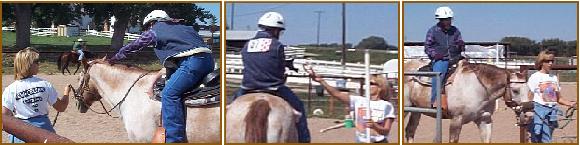

Using a platform, three staff members help student Gary onto Riley.

Using a platform, three staff members help student Gary onto Riley.

|

The first big step is to get the student on the horse. It may take several sessions of sitting outside the corral, watching and mustering courage before this moment. It then takes three people; one to hold the horse, one to hold the student, and one to act as "the wall" should the student climb up one side of the horse and start tumbling down the other side.

After Gary mounts his horse, Clark leads him to the riding ring, where they take a few half-laps to warm up. Three other students are in the class today, all of whom are comfortable riders. Each student has a volunteer "side walker" to lead him or her, and the instructor, Deb Riley, directs the class. Clark leads Gary around the ring several times, helping him to relax and have more control on the horse. She takes him through a course involving tricky turns and graceful maneuvers. She has him stretch to touch the horse's ears - an awkward and precarious move. She runs alongside as Gary puts his steed into a trot. The class goes very well and the students are rewarded with a trail ride around a part of the center's 36 acres - Clark will walk for several miles today.

Any cowboy will tell you that a ride in the saddle is good for the soul.

Any cowboy will tell you that a ride in the saddle is good for the soul.

Helen Clark helps Gary through a class, in stretching, placing rings, and heading out on the open trail.

Jody, who is mildly retarded, autistic and suffers from seizures, is riding an older horse, named Miss Pearcy. She lumbers along with a huge smile glued to her face the entire hour. "I love this center!" says her mother, Mary Ann Menoher. "There has been a great difference in Jody's posture since coming here." Something as seemingly simple as a change in posture can mean dramatic improvements in the life of a person like Jody, and even in the well-being of their family.

The Colorado Therapeutic Riding Center also offers classes to children who are in detention facilities or are headed that way. With a degree in Psychology and Corrections, Clark enjoys working with "at-risk" youth. "They are having trouble controlling their own lives and you put them on a huge horse," she says, "It's a strong builder of cooperation and trust."

Not content with only the deep rewards of teaching students, or with cleaning the stables, Clark is on the center's board of directors and she handles the dreaded task of fund raising. In her sixth year at the center, she has set her sights high, trying to raise enough money for an indoor arena - she hopes that being able to teach classes year-round might shorten the center's 12-month waiting list. Though over 100 people volunteer at the center, it still takes a lot of money to run it and improve its facilities. Student fees are on a sliding scale, starting at $200 per ten-week session, which pays for about half of the center's expenses, says Hodgkins, and the rest is raised through donations. People around here do love horses, and the support level is very high.

Not content with only the deep rewards of teaching students, or with cleaning the stables, Clark is on the center's board of directors and she handles the dreaded task of fund raising. In her sixth year at the center, she has set her sights high, trying to raise enough money for an indoor arena - she hopes that being able to teach classes year-round might shorten the center's 12-month waiting list. Though over 100 people volunteer at the center, it still takes a lot of money to run it and improve its facilities. Student fees are on a sliding scale, starting at $200 per ten-week session, which pays for about half of the center's expenses, says Hodgkins, and the rest is raised through donations. People around here do love horses, and the support level is very high.

Clark's husband is a doctor, and since the couple has no children, working at the Colorado Therapeutic Riding Center gives her a connection to life that she would not ordinarily have. She enjoys working with the horses, but more so with the students. "Here you get kids of all kinds on their good days and bad," she says. Clark routinely works with and improves the lives of people with Attention Deficit Disorder, Autism, Multiple Sclerosis, Cerebral Palsey, and closed head injuries. She also works with developmentally delayed adults and at-risk teens. "I'm learning something new every day," she says.

Helen Clark is also rewarded every day. Each time she helps a person achieve even a small goal, and each time she sees growth in someone for whom growth seemed impossible, she feels a well-deserved pride. She is rewarded each time she enables a person to climb onto one of these magnificent animals and fly away, to rise out of a world of confinements and inabilities, and into a world filled with possibilities.