America Eats Here

Wednesday, July 22, 1998, New Haven, Connecticut -

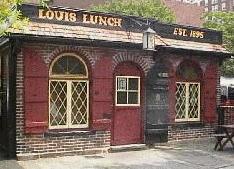

You enter the tiny building of Louis' Lunch, a few blocks south of Yale University as you would enter your home, because this is home for you.

Wednesday, July 22, 1998, New Haven, Connecticut -

You enter the tiny building of Louis' Lunch, a few blocks south of Yale University as you would enter your home, because this is home for you.

You sit down at one of the five barstools or the twenty or so benches in the place and you sit there because it is your seat, and has been for years. If somebody has the nerve to be sitting in your seat, you sit in your other seat. They are all yours, because this is your home.

You hear a "YES-sir" from behind the counter each time the front door opens. It is Ken Lassen, who is the grandson of the late Louis Lassen, and who now handles the business side of this operation. He is pulling orders from people as they enter, because the line is practically out the door. Ken has already put in your order - a cheese-works and a cream soda - because that is what you always order and that is what you're going to get.

"I've been coming here for sixty years," your friend, Ed Lyons, tells you. "I'd like to change my order, but I can't."

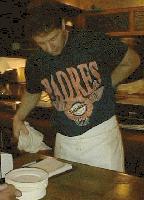

Ken Lassen carries on the

austere tradition of the world's

first hamburger restaurant.

But there are people behind you, and they are new here, and they fumble with their orders. There isn't much to fumble with, but they do, and you forgive them, because this isn't their home - not yet. Even they don't order fries or onion rings or salads, because they can't. Just hamburgers - this is where the American favorite was invented nearly one hundred years ago and since then, no one in their right mind has come in here asking for anything else.

Someone asks you about this place and you tell him, because it's your story and you're proud of it. You tell him about how, in 1900, a man rushed into this very building and asked for a quick meal that he could eat on the go. Then you tell him about the original owner, Louis Lassen, like he was your grandfather, because he is, and how Louis put a patty of broiled beef between a couple slices of bread and, in that instant, he changed the way America eats. And you are animated as you tell this story because you are so proud.

Mom works on your burger, as she has worked on a million hamburgers before yours. Though you don't know it's your burger because she is working on so many. No, you won't know it's your burger until it sits in front of you on a paper plate.

"Mom" Lassen, wrapping up two of

America's orginal hamburgers,

has served enough of these sandwiches

to feed a large country.

Mom tosses some bread in the top of the automatic toaster and retrieves a few pieces of toast from the bottom. She mashes a meatball into a patty and she does this several times more, placing the patties between two hinged, wire grills. Popsi, who is Louis' son, Ken's father and Mom's husband, ground the beef fresh for you this morning.

Yes, your favorite little restaurant on Crown Street has been run by the same family since it opened. When you come here, you don't expect shallow courtesies, as part of the atmosphere comes from the Lassens ordering the customers around, treating them like, well, family. You remember Celeste Denison telling you why she and her husband have been coming here for twenty-nine years; "The food's good and the people are great," she said. "You become part of the family."

Mom sandwiches the patties between the grills and puts this aside. She then opens one of the hundred-year-old gas ovens that have been the workhorses of Louis' Lunch for a century, and she pulls out a grill with freshly cooked hamburgers in it, each cooked medium-rare because that's the way Mom cooks them.

She unfolds the grill and spatulas the burgers onto slices of toast. On some toast she has spread cheese, on some she drops onion or tomato, because that is how Mom makes them and a fool might suggest otherwise. She then covers each with another slice of toast and puts them on paper plates and says to Ken; "these are Dad's," as she has said a thousand times.

Two of the ovens in use

at Louis's Lunch since it's opening in 1895

Ken stacks three burgers, separated with paper napkins, grabs the stack in one hand and reaches over you. You duck, as you have done for years, then you reach up, grab the stack of burgers and pass it back to three young guys ("Dads") in the booth by the west window, because this is their lunch.

The man next to you says, "this place sure is small!" and you start in with your second favorite story about how it once was even smaller - only about ten feet wide - when it was down the street. You point to a high-rise building, the very building that sits where you once sat - in this very building - and you tell the man how they wanted to destroy Louis' little lunch restaurant to put that building there.

Your hamburger arrives with cheese, tomato and onion on it and you take a bite, as you have done a thousand times. You don't put ketchup or mustard on your burger, because you can't, and, of course, you don't want to. You remember your friend, Bailey, telling you; "my husband asked for ketchup once - they almost killed him." You enjoy your burger, as it is delicious, as they have always been.

Then you tell this man about how you and the city rallied behind Louis and refused to let this landmark die and how you put the tiny building on a truck and moved it to this very place.

Tears may well-up, but you continue your story. You point to the east wall and tell this freshman how that entire half of this little restaurant is new and how it was built with bricks donated by you and other loyal patrons. And you point to your bricks and tell him that they are from a church in England, or a street in the Bahamas and you point to other bricks, brought by other people from everywhere. The place is made of bricks from around the world; appropriate, you say, because the hamburger is enjoyed by people all over the world.

You've spent way too much time in your seat and it is now someone else's seat and Mom growls at you; "Will you eat your sandwich and shut up?" and you go on talking, because that is what you have done for years.

CONNECTICUT'S MANY ACHIEVEMENTS

- Sewing Machine - 1846, Elias Howe

- Submarine - 1775, David Bushnell

- Public Library - 1656, in New Haven

- Newspaper, oldest continuously published - 1764, Hartford Curant

- Typewriter - 1843, Charles Thurber

- City Park- 1854, Horace Bushnell (Hartford)

- Condensed Milk - 1856, Gail Borden

- Can Opener - 1858, Ezra Warner

- Cork Screw - 1860, Philos Blake

- Insurance - James Goodwin Batterson and the Travelers Co. 1864

- Pay telephone - 1877, William Gray

- Lollipop - 1908, New Haven. Named after a famous racehorse

- Frisbies - 1920, by Yale students flinging empty Mrs. Frisbie's pie tins.

- Helicopter - 1939, in Stratford

- LP record album - 1948, Peter Goldmark

Source: Connecticut First, Wilson Faude & Joan Friedland, 1978

|