Working Like a Dog

Clyde Risdon shows off one of his first sleds, made in the early eighties.

Behind him is one of his newer models.

Even if you have given up fur trappers and carrying mail and freight over frozen tundra, you may still want to park one of these beauties in your garage. Dog sled racing is a growing sport, attracting people from around the globe. "We sell a lot of sleds in California," Risdon says.

A tool and die maker in the Upper Peninsula in the seventies, Risdon was an avid dog sled racer. The more he raced, the more he believed that he could build a better sled than the one he was using, and so he did.

First, he made a few "wheel rigs;" metal carts with large, soft wheels that can be towed (and ridden) over most surfaces and which are useful for training dogs when there is no snow. Then, he built a few wooden sleds and began selling them in 1980, the year he stopped racing.

One of his first customers was Harris Dunlap - "one of the first guys who made a living racing," says Risdon. Dunlap used a Risdon sled, or "rig" in a race. His endorsement sold fourteen "Risdon Rigs" faster than a team of hungry Labs, and Clyde Risdon had himself a new career.

It has been a good career, as his sleds are popular among professional racers. DeeDee Jonrowe, the first woman to run the Iditarod, has raced a Risdon Rig for years and she is only one of his many racers. "A few years ago, we would look through the medal winners and half of them used our sleds," he says. "We're getting stiffer competition now."

A dog sled is a beautiful machine full of compromises. It must be lightweight, yet it must be strong. It must be solid, yet it must be flexible. It must carry a person and sometimes hundreds of pounds of gear and food over rough terrain in some of the worst conditions and it must do this sometimes at twenty to thirty miles an hour.

Tuesday, September 8, 1998, Lansing, Michigan -

When shopping for your next dog sled, keep in mind that there are more sleds made in Michigan than anywhere in the world. That is the claim of Clyde Risdon and he should know, as he makes nearly one hundred each year.

Tuesday, September 8, 1998, Lansing, Michigan -

When shopping for your next dog sled, keep in mind that there are more sleds made in Michigan than anywhere in the world. That is the claim of Clyde Risdon and he should know, as he makes nearly one hundred each year.

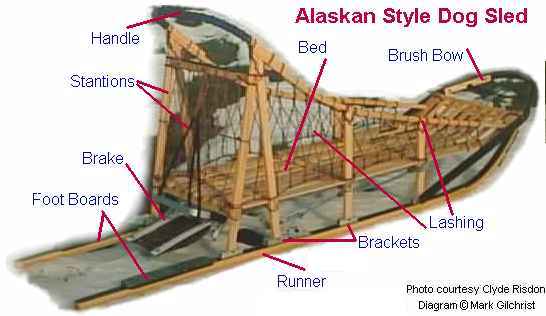

Risdon assembles sleds by lashing most of the joints together. He now uses aluminum brackets to secure his stantions to his runners, and he also uses stainless steel, graphite and Ultra High Molecular Weight plastic in his sleds. But the bulk of each sled is still wood.

Risdon's choice of wood is white ash. "For the weight, it's about the strongest thing going," he says. He carefully selects only white ash with a straight grain and thin growth rings. Any material that doesn't meet his standards, he uses "to heat the shop."

He says he will probably begin using more aluminum, graphite and possibly titanium, with which he is now experimenting. "In the last few years, things have been changing fast," Risdon says. "When we started, fifteen miles an hour would have won a race. Now the average is seventeen and they go as fast as twenty-five and thirty miles an hour. The Iditarod takes only nine days, not the fifteen days it once took."

Risdon attributes this incredible increase in speed to improvements in four areas; breeding, feeding, training and trails. He admits that sled design has only had a modest effect on speed, but, because of the greater speed, sleds today suffer a lot more punishment and must handle much better.

"That's what our sleds are known for, the handling," he says. "They corner good and they go good on the straight stretches." Risdon Rigs are also known for durability, and Risdon warranties his runners for five years. "We don't care if you run over it with the truck," he says. "We'll replace it."

The "we" includes Pat Risdon, Clyde's wife, who helps make the rigs in their small shop in Laingsburg, Michigan. They offer a dozen models, ranging between $500 and $1,000.

The average Risdon Rig weighs 22lbs. The Protracker, his most popular model, which folds and ships easily, weighs 23lbs. He can make his sleds a few pounds lighter, but the trade-offs in handling and durability are not worth it. It is apparent that Clyde Risdon enjoys the challenge of designing a better, faster product for his customers.

Changing with the times - The Protracker.

Ridson doesn't race sleds much anymore, the last time was three years ago for a 42 mile race. "It's addictive," he says. "Both of the last times I've raced, I've thought I ought to get a few dogs and go to this. To make it worse, my wife is all for it.

"But it's too much work," Risdon says. "By the time you train, feed, clean up and all, you spend four to six hours a day." It is obvious that, even though he can no longer race, he enjoys making sleds; carefully shaping the woods and assembling these beautiful machines.

Clyde Risdon doesn't hope to give the sled building business to his children. "I don't see any of them being interested in this - there's not enough money in it. I'd be kind of disappointed if they did." He will continue making dog sleds as long as it remains a labor he loves, which is why he enjoyed racing; "It's great to watch dogs who work because they want to," he says. "You stop and they stand there in their harness barking and barking like they want to go again."

Traditional racers abhored synthetics, but

Risdon's most popular sled today uses plastic

and other materials not found in the woods.

It even folds!

Check out the

True America Made in the U.S.A. Archives

Return to our

MAIN page