Harvest of the Heart

He likes riding with dad, because his dad likes riding with him. At only 3mph, it is not a thrilling trip, but it is fun; the great noise of the diesel engine, the craziness of the twenty foot long sickle cutting the crop and the huge auger pulling it in - right in front of them. And the window behind him, through which he can see the little beans pouring into the hopper like rain. He doesn't know how important this rain is. He doesn't yet care.

Whether good or bad, the harvest is always the end of the anxiety that builds up during the summer and spring, it is the landing of the dice that have rolled for five long months. Whether good or bad, the harvest is always a time to see the product of your labor of the past year, to work the machines you have repaired for months and to give the world a special gift, one which only a farmer can give.

To be a farmer, you have to be in touch with your heart and know what it is that you really love. Then you have to stick with it no matter what. Van Bergen loves to grow the food on which his country will survive. He loves to work with machinery and tools and he loves to be his own boss. "There's nothing like working for yourself," he says. "If I want to take a day off and spend it with my son, I can - not during harvest, of course. If something screws up or breaks, I did it."

Bergen Acres is a short drive west of Chicago, short enough to become the target of urban sprawl. The cornfield I slept in the night before was being sold for an office park. "Land out here is going for five thousand an acre," says Bergen. "That may not be much for a home, but it's a lot for a guy like me to make a living farming!"

The Bergen family knows the effects of urban sprawl. Mike Bergen's parents raised their family in Elk Grove Village, growing onions, beets and other produce and trucking them into the Chicago market - "truck farming" he calls it. In the 1960's, the Bergen land was condemned to build O'Hare Airport, and they moved out here.

I do not have to worry about how much I am harvesting. Sometimes, I am taking in over fifty bushels per acre, and sometimes when the earth below us is more gravel than soil, my yield drops to twelve or thirteen bushels, but that doesn't bother me. The combine I am driving, a 1990 Case IH 1660, costs over $60,000 and will burn over 100 gallons of diesel today and I won't care. If the moisture of the beans gets over 13%, the buyer will penalize Bergen and discount the price he gets, but he has to worry about that, not me. We sometimes hit a patch of blight - I just give the dead crops a curious look.

I will be a farmer for only an hour or so, when I will get on my bike and lead another life. Bergen will work until late tonight, weather permitting, and will rise tomorrow to do this all over again.

And when I sleep tonight, I won't go there thinking about expenses, such as: seed, fertilizer, insecticide, herbicide, insurance, interest, labor, equipment, fuel and cash rent, most of which stay fixed, even if the crop turns to weeds.

"The price of soybeans is half of last year," says Bergen. "Last November, we got $7.27 a bushel. This year, we'll be lucky to get five dollars. Corn was $2.70 and now it's down to $1.60." The Bergens have hedged against the volatile market. "We have puts and calls on the board of trade," he says. "My banker recommended it, and I'm sure glad we went with it because it's crazy how the market has been going."

Soaring land prices, a volatile market, competition from overseas and from huge, corporate farms, and a greater variety of other professions are some reasons for the steady reduction in the number of midwestern family farms. "A lot of farms around here are going out of business," says Bergen. "I know only three guys my age who are farmers." Van Bergen is on the McHenry County Farm Bureau to help the state of farming in the area.

Farming has become very hi-tech, meaning it has become more complicated and expensive, and the need to keep up with this technology is demanding. In the cab of the combine (a combine is a combination of a harvester and a thrasher) is a digital readout, fed by sensors throughout the large machine. From this, Van Bergen knows, in real time, what his yield is per acre and the humidity of the crop he is harvesting. He can store this information and analyze it on a computer. Using GPS, the company that sprays his fields with insecticides and herbicides knows exactly where to spray.

Each year brings a new season of life to this part of the country. Springtime yields small seedlings of corn, soybeans and many other crops. Through the summer, the roadsides come alive, sprouting, growing, filling your entire perspective with verdant fields of thriving plantings. It is breathtaking to drive through here, the "breadbasket of the world" and see how those vegetables you take off the grocery store shelves are born. Summertime is a gentle, silent ride over the rolling hills, only the wind through the stalks of corn to sing to you.

Early fall is not a good time to die, not for a farmer. Given the choice, any man would say; "God, please, let me take in the harvest for my family first, then you can have me." Most are not given that choice, and sometimes a woman and her children are suddenly left with nothing but a whole lot of crop.

Leon Schwinn was not given a choice, and he recently passed away, leaving seventy acres of ripe soybeans sitting in the sun. That's the way life is out here; you count your blessings, not your days. Mrs. Schwinn and her two sons had no way of harvesting the crop themselves. As you might guess, this is not a problem around here.

Mike Van Bergen and Rich Jacobson are in Van Bergen's shop, studying the radar images of McHenry County. It is the middle of the soybean harvest for them, and they each have large fields to harvest, with only a few days left. The weather is not cooperating. Soybeans cannot be harvested if the air is too moist - the beans' humidity has to be below 13% or the farmer is penalized at market. The image on the screen shows rain clouds coming their way and this upsets them.

"There's the rain we got this morning," Van Bergen says. "That messed us up bad."

"What does it look like for tomorrow?" says Jacobson. Van Bergen tries to load another screen, but can't get a forecast.

"See these clouds here? This afternoon is shot. We'll have to wait."

Van Bergen and Jacobson are nervous about the weather. Between them, they have well over a thousand acres of soybeans to collect before the next week is out. But their anxiety right now is from the problem at hand; when can they get a large enough window of dry air to bring their combines and other equipment over to the Schwinn farm and bring in their harvest for them?

The next afternoon, the weather has cleared and the stretch of Kemman Road to the Schwinn farm has come to life. As the sun falls toward golden fields, several combines roll across the horizon. Mike Van Bergen, Rich Jacobson and George Rudolph pull their great machines onto the Schwinn property and get right to work. Stade Grain Company brings trucks to carry the soybeans to market and Roger Bottomly is there to help Glen Schwinn keep things moving.

It would take one man over ten hours to harvest this crop, but this team will get the job done in three or four hours, if the weather holds. By 6:30 the humidity climbs over 13% and the farmers park their machines and head home. After a few hours of working on their farms, they will go to sleep, get up tomorrow and return here to finish it off.

Quinten Van Bergen may become a farmer someday, just like his father. Right now he likes to ride in the combine, playing with his toys on the floor of the cab, watching the world's next meal being prepared in front of him. When he is old enough to decide how he will spend his life, he should know that, to be a farmer, it takes technical acuity, marketing savvy and determination, and it will always take a big, powerful heart.

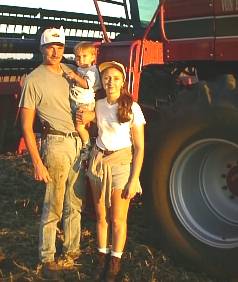

Mike, Quinten and Tracie Van Bergen.

Check out the

True America Made in the U.S.A. Archives

Return to our

MAIN page

|

Soybean harvest is a nice time for Mike Van Bergen. The rest of the year he spends getting ready for these ten days. The rest of the year he holds inside him worry and hope for a good harvest; he watches the weather, he studies the market, but he never knows how his entire year will be until these ten days in late September.

Soybean harvest is a nice time for Mike Van Bergen. The rest of the year he spends getting ready for these ten days. The rest of the year he holds inside him worry and hope for a good harvest; he watches the weather, he studies the market, but he never knows how his entire year will be until these ten days in late September.

Bergen farms 900 acres of soybeans, 850 acres of feed corn and 150 acres of sweet corn. His parents also farm 100 acres of produce for the family's stand. Of the 2,000 acres, the Bergens own only 90. They "cash rent" the rest, mostly from the Mormon Church. "Most of the farmers I know cash-rent their land," Bergen says. "it doesn't make sense to tie up that much capital in land anymore."

Bergen farms 900 acres of soybeans, 850 acres of feed corn and 150 acres of sweet corn. His parents also farm 100 acres of produce for the family's stand. Of the 2,000 acres, the Bergens own only 90. They "cash rent" the rest, mostly from the Mormon Church. "Most of the farmers I know cash-rent their land," Bergen says. "it doesn't make sense to tie up that much capital in land anymore."

I am a farmer today. Van Bergen lets me drive his combine, and I harvest over a hundred bushels of soybean. Of course, I am not a real farmer, but this is the closest I've ever been.

I am a farmer today. Van Bergen lets me drive his combine, and I harvest over a hundred bushels of soybean. Of course, I am not a real farmer, but this is the closest I've ever been.

I don't have to worry about the fleet of equipment, such as the new tractor that costs over $100,000, trucks, grain wagons, portable fuel tanks, or buildings, such as the $160,000 grain elevator, or two-way radios, tools, insurance... not to mention the price of beans.

I don't have to worry about the fleet of equipment, such as the new tractor that costs over $100,000, trucks, grain wagons, portable fuel tanks, or buildings, such as the $160,000 grain elevator, or two-way radios, tools, insurance... not to mention the price of beans.

Bergen has a satellite-fed monitor in his shop to show him detailed radar weather of McHenry county and the state, as well as up-to-the-minute quotes from the commodities market. He keeps a cellular telephone with him to keep in contact with workers, contractors and his family.

Bergen has a satellite-fed monitor in his shop to show him detailed radar weather of McHenry county and the state, as well as up-to-the-minute quotes from the commodities market. He keeps a cellular telephone with him to keep in contact with workers, contractors and his family.

Fall is a time of harvest. Huge machines roll through the countryside, cutting down the crops and collecting their bounty. It is the time when all that life passes on, to provide us with food for our lives.

Fall is a time of harvest. Huge machines roll through the countryside, cutting down the crops and collecting their bounty. It is the time when all that life passes on, to provide us with food for our lives.